Why does stability matter in cycling performance? Should we all spend a bit more time on one leg in 2019?

Learn how you can test your balance and stability yourself at home and begin some simple work to improve your riding!

As more of us are beginning to train with ever more sophisticated power meters, giving us more information than ever to understand our performance, it is important to understand what exactly goes into generating the forces we are measuring and analysing. Why do you feel like one leg is ‘smoother’ or ‘works better’ than the other one? Why does your power meter always show a 47%:53% split in power production left vs right? Why can’t your knees stay in a straight line when you push down on the pedal?

As cyclists we often obsess about and aim for symmetry. Symmetry of pedalling technique, joint angles during bike fit and power output. Before continuing it is important to realise that in many ways human beings are not symmetrical and that perfect symmetry in everything we do on the bike may A. not be possible and B. may not always improve performance and reduce injury risk.

There are many reasons why an individual may not present in the same way on both sides of the body. Environmental factors include; the type of work we do, how long we spend doing certain activities where one side is used more than the other and sporting background. Intrinsic factors can include; neurological dominance, biomechanics, injury history, and whilst rare, skeletal asymmetry.

It is commonly accepted however that significant asymmetry in movement patterns can lead to increased joint and tissue loading and therefore increase the risk of injury. It is therefore still a valid goal in training to reduce any discrepancy in physical conditioning between the two sides of the body in order to perform optimally and this could be especially important in endurance cycling.

So, where does balance come into all this?

Without boring you all to death here it is important to cover some basic anatomy. The skeletal system is a collection of bones with a goal of protecting vital organs and which come together at joints to provide articulation for movement. There are different types of joint. Some, like the knee, are hinge like joints which allow only 2 main movements, flexion and extension (opening and closing). Other joints allow movement in multiple directions like the ball and socket of the hip joint.

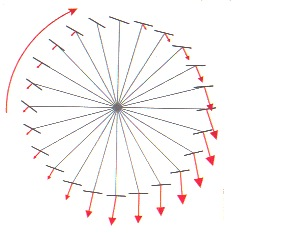

The muscular system can be viewed as an an interwoven network of large power producing muscles with smaller stabilising muscles alongside. The larger power producing muscles generate the force, the smaller stabilising muscles work to make sure the force is delivered in the right direction. In cycling the gluteals and the quadriceps should be contributing the majority of force in the drive phase of the pedal stroke (12-6 on a clock face) to extend the hip and knee in the saggital plane. However if the stabilising muscles of the hip, ankle and foot aren’t doing their job then it can be difficult to control the movement in the required direction and movement can occur that does not help to push the pedal down. In this case more energy can be used than necessary and lower forces are transferred to the pedal to push the bike forward therefore reducing efficiency and impacting performance.

In many ways the mechanism of pushing the pedal down is similar to the action of standing up from a chair on one leg. Both movements require a combination of hip and knee extension from a position of flexion. In pedalling as we push on one pedal the opposite leg should be switched off before then switching the extensor mechanisms on again around 12 o’clock to engage its drive phase. So effectively pedalling is also a single leg activity. This is repeated quickly around 80-90rpm. (I must stress here that for the purpose of this blog post this is a rather simplified view of pedalling dynamics during steady state cycling and that there are clearly some caveats with situations that require both ‘push and pull’ under different loads or terrain. For more information on pedalling dynamics please see work of Dr Jeff Broker and Prof. Jim Martin and many others who are experts in this field.)

If we break down the components of the push phase of the pedal stroke from a physical conditioning point of view it can be said that in order to produce force there must be:

- Adequate strength and endurance of the hip extensors (glutes) and knee extensors (quads) to create movement

- Adequate strength and endurance of the ankle plantar flexors (calfs) to hold the foot and ankle in a static position to transfer the forces from above to the pedal

- Effective activation and endurance of stabilising muscles of hip/pelvis and foot/ankle

- The co-ordination and control to put all of the above into action at the same time

For optimal performance of the drive phase in cycling the athlete must have all of the above. You could have the biggest and strongest quads in the world but if you don’t have good static calf strength or co-ordination then efficiency may be compromised and injury risk could increase.

The more technical term for co-ordination and control that we are talking about here is proprioception.

Proprioception: the perception and awareness of the position and movement of the body.

Knowing where your body is in space is key in the ability to balance and to remain stable on single leg activities. There are sensors in muscle, tendons and at each joint which pass information back to our brains which we then use to co-ordinate the stimulation of stability muscles to keep us on the straight and narrow.

The good news, and finally the point I am trying to make in this piece (in a very long winded way), is that this can be improved and is often over looked in our off bike training. For some of the reasons mentioned above we may be better at this on one one leg vs the other and this may help to explain some of the imbalances we feel on the bike. Understanding more about you ability to balance and your lower limb stability could improve your riding. After all ‘you wouldn’t fire a cannon from a canoe would you?!’

The Tests

The goal of these tests is to help you understand more about your body and help give you some answers as to why you may notice some asymmetry on the bike. If you do find some differences and you want to understand this further then please do not hesitate to get in touch.

The tests are progressive i.e test #3 is harder than test #1 so it may be best to try them in order.

Please note that these test require physical effort and should not be attempted if there is any reason why you should not attempt physical activity at this time. If at any point there is discomfort during these movements then please stop and seek the advice of a medical professional. Physiohaus accepts no responsibility for any issues that may arise as a result of attempting these tests.

Test #1 Single Leg Stand

- Stand on one leg with shoes off and your hands across your chest

- Balance for as long as you can

- Record time

- Repeat on opposite leg

- Complete 3 attempts and note your best time on each side

IS THERE A DIFFERENCE IN TIME?

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE- BALANCE, FATIGUE, DISCOMFORT*?

There is no real expected time that you should be able to stand on one leg for, the important thing is whether there is a difference. As a very rough guide a well trained individual should be able to stand on one leg for around 1:30min.

If there is a difference then it could be worth practising to balance more on the more difficult leg more regularly with the goal of closing the gap in time. You could retest at regular intervals to check your progress.

*If there is any discomfort at any time when doing this then please stop and consult a medical professional

Test #2 Single Leg Partial Squat

- Stand on one leg with shoes off and your hands across your chest

- Bend knee so that when you look down you cannot see your toes any more

- Repeat x 10

- Repeat on opposite leg

IS THERE A DIFFERENCE IN HOW EASY IT IS TO DO THIS ON EACH LEG?

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE? BALANCE? DOES THE KNEE MOVE IN OR OUT MORE ON ONE SIDE COMPARED TO THE OTHER? DISCOMFORT*?

In an ideal world you should feel the same when doing this exercise on both legs. You should feel equally as stable and the knee lateral movement should be minimal.

If there is a difference than it could be worth practising this moment more regularly on the more difficult leg with the goal of closing the gap in ability. You could retest at regular intervals to check your progress.

*If there is any discomfort at any time when doing this then please stop and consult a medical professional.

Test #3 Single Leg Sit to Stand

- Sit on chair with shoes off. The chair should be the correct height to roughly put your knees and hips at a 90 degree angle

- Take one foot away from floor and cross hands across chest

- Lean forward and and stand up on one leg

- Slowly return to start position on one leg

- Repeat up to 10x

- Repeat on opposite leg

IS THERE A DIFFERENCE IN HOW MANY REPETITIONS YOU CAN DO? HOW EASY IT IS TO DO THIS ON EACH LEG?

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE? BALANCE? DOES THE KNEE MOVE IN OR OUT MORE ON ONE SIDE COMPARED TO THE OTHER? DISCOMFORT*?

In an ideal world you should feel the same when doing this exercise on both legs. You should feel equally as stable and the knee lateral movement should be minimal.

If there is a difference than it could be worth practising this moment more regularly on the more difficult leg with the goal of closing the gap in ability. You could retest at regular intervals to check your progress.

*If there is any discomfort at any time when doing this then please stop and consult a medical professional.

Photo Credit: Russ Ellis

Blog Credit: Morgan Lloyd, MCSP, MACPSEM Physiotherapist, Bike fit Specialist and Educator