What is the ACL

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) is one of the key stabilising ligaments in the knee. It helps control forward motion and rotation of the tibia relative to the femur. Because of the demands placed on the knee in many sports (cutting, landing, pivoting), the ACL is vulnerable to injury.

Causes of ACL Injuries

ACL injuries can occur via several mechanisms:

- Non‐contact injuries: sudden deceleration, change in direction, pivoting, landing from a jump with improper alignment (knee valgus, internal tibial rotation).

- Contact injuries: direct blow to the knee (from another player or object), hyperextension.

- Risk factors:

- Biomechanical: poor landing mechanics, weak hip abductors/glutes, weak core.

- Neuromuscular: delayed muscle activation, imbalance between quadriceps and hamstrings.

- Anatomical: narrow intercondylar notch, ligament laxity.

- Hormonal: some evidence of differences in ACL injury risk in females associated with menstrual cycle phases, hormones.

- External: tiredness, playing surface, type of footwear.

Symptoms & Diagnosis

- Symptoms often include a “pop” sound, immediate swelling, pain, instability (“giving way” when trying to pivot or change direction).

- Diagnosis usually via physical exam (Lachman test, pivot shift), imaging (MRI for soft tissue delineation).

Management Options: Conservative vs Surgical

Management depends on several factors: patient’s age, activity level, degree of instability, associated injuries (meniscal tears, cartilage damage), personal goals.

Conservative (Non‐Operative) Approach / Rehabilitation

- A non‐operative approach may suit people with low activity demands, those willing to modify activities, or those who accept some instability.

- Key components:

- Initial phase: Swelling control, pain management, restoration of range of motion (especially extension), reduce inflammation.

- Strengthening: Quadriceps, hamstrings, hip muscles. Emphasis on hamstring strength to protect the knee.

- Neuromuscular training / proprioception: balance, coordination, improving movement patterns to avoid risky mechanics.

- Gradual progression to functional tasks: low‐impact exercises, later more dynamic sport‐specific drills.

- Pros: avoids risks of surgery (infection, surgical complications), less cost, no graft harvest morbidity.

- Cons: possible persistent instability, increased risk of secondary injury (e.g. meniscal tears, early osteoarthritis), may limit return to certain sports.

Surgical Intervention

- Standard when instability is problematic, especially in active individuals, athletes, or when there are associated injuries.

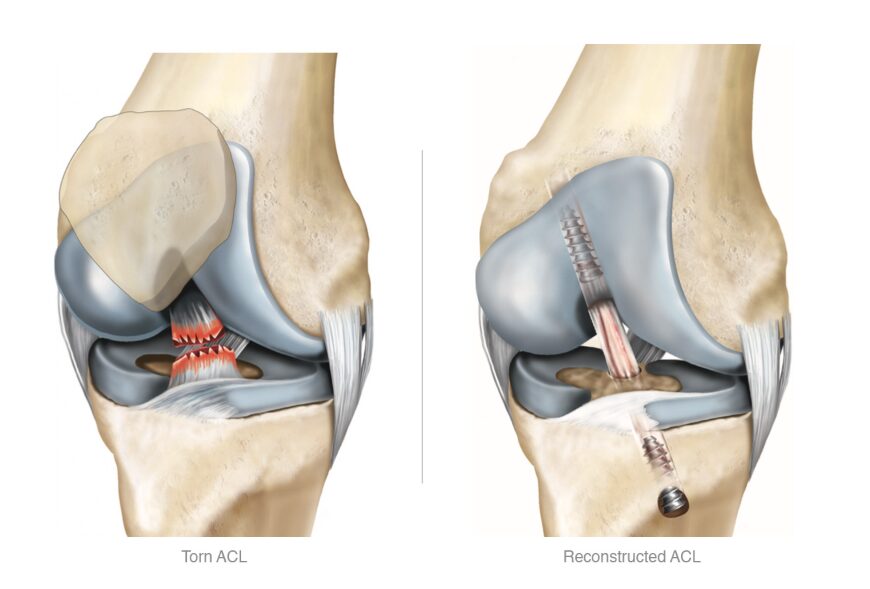

- ACL reconstruction typically involves grafting (autograft—e.g. hamstring tendon, patellar tendon, sometimes quadriceps tendon; or allograft) to reconstruct the torn ligament.

- Key surgical considerations:

- Choice of graft type (pros & cons in terms of strength, donor site morbidity).

- Tunnel positioning, fixation methods.

- Addressing any associated meniscal/cartilage damage.

- Post‐surgery rehabilitation is crucial.

Rehabilitation After ACL Reconstruction

Good rehab is essential to surgical success. Key phases include:

- Immediate post-operative phase: Protect graft, control swelling, regain extension, begin safe activation of muscles.

- Intermediate phase: Increase strength (especially hamstrings, gluteal muscles), restore range of motion, begin proprioceptive/balance training.

- Advanced strengthening and agility: Plyometrics, dynamic movements, sport‐specific drills.

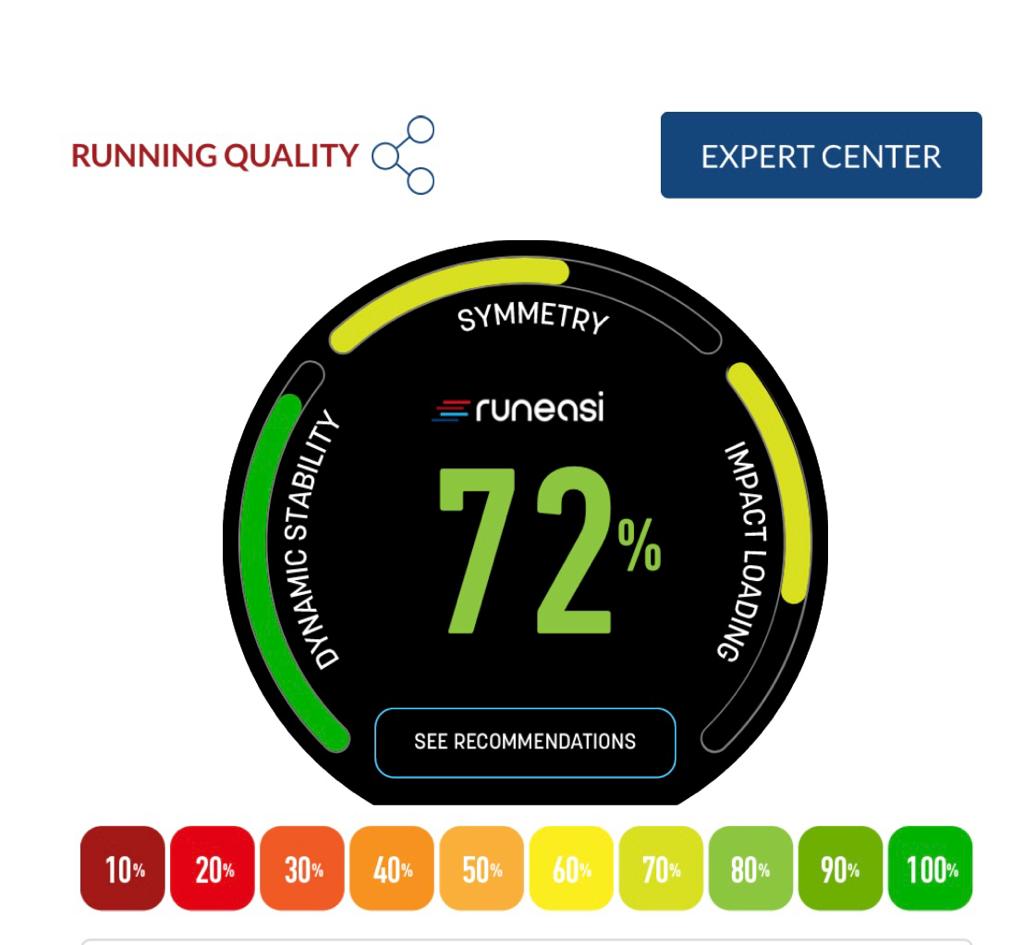

- Return to sport: Objective testing (strength symmetry, hop tests, movement quality), psychological readiness.

Challenges include patient adherence, fear of re‐injury (kinesiophobia), access to high‐quality physical therapy / support.

Tips for Best Outcomes

- Early diagnosis and appropriate decision‐making.

- Access to high‐quality physiotherapy, with progressive, structured programs.

- Focus on neuromuscular training to prevent risky mechanics.

- Monitoring strength and function objectively.

- Address psychological factors — fear of re‐injury, motivation.

- Ensuring patient understands expectations: return to sport often takes many months (often 9–12+ months in many high‐level contexts).

Conclusion

ACL injuries are common, often serious for active individuals, but good management (surgical or non‐surgical) plus high‐quality, patient‐centred rehabilitation can lead to good functional outcomes. Recent research emphasizes not only the mechanics and biology, but also the psychological and service delivery sides of rehab.

What next?

Book in for an initial assessment with the team or get in touch for more information.

Looking to return to sport after ACL injury? Check out our blog on how we use force plate testing to ensure the best chance of success.